As companies consider their strategies for life in a post-Brexit world, our study reveals the projected impact of hard Brexit in four sectors that are key to UK manufacturing and our clients: the automotive, consumer, healthcare and technology industries.

For the purposes of the research, we focused on a hard Brexit in order to draw the strongest possible contrast between continued membership of the Single Market and a Brexit in which we leave the EU customs union and bilateral tariffs revert to WTO ‘Most Favoured Nation’ levels.

Key findings:

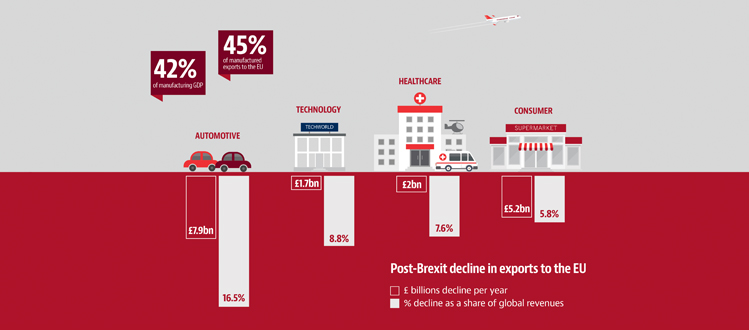

- Across the four sectors we modelled, hard Brexit would lead to a fall of almost £17 billion in annual EU export revenues

- Increased costs of exporting to the EU, in the form of both tariff and non-tariff barriers, would total £3.8 billion across these four industries

- The proportionate fall in UK global exports would be four times that of EU exports in key manufacturing sectors

- New trade deals with third markets could offer the best opportunities for UK exports – particularly the United States

- UK manufacturing exports to target third markets would need to increase by 60% to offset ‘hard Brexit’ EU export losses

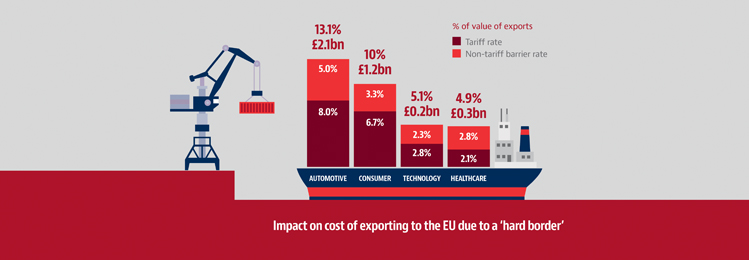

If a hard border were imposed between the UK and the EU, companies that once traded freely with European markets would see their goods exposed to new costs each time they cross the channel. These costs would take the form of both tariff and non-tariff barriers. We would expect companies to take steps to offset these added costs, for example, by increasing their domestic sales or exporting to new third markets.

However, if exports to the EU continued at the same level as in 2016, these added costs would amount to a total of £3.8 billion per year across the four key manufacturing sectors we modelled. As a result of that potential cost, EU export revenues in those sectors would decline by a total of almost £17 billion per annum.

As a result of reduced trade between the UK and the EU, companies in the four UK manufacturing sectors we modelled would see a decline in their global export revenues of between 10% and 24%.

By contrast, EU global exports would fall no more than 7.3% as a result of reduced trade with the UK, or no more than 2.5% adjusting for increased trade within the remaining European Member States.

“We have heard a lot about how much Europe exports to the UK, for example, in the automotive sector,” says Ross Denton, Baker McKenzie trade partner. “That may be true in numerical terms, but when you look at this as a percentage of their trade, you can clearly see that the EU exports a lot more broadly, to a whole host of other markets, and consequently, it is far less dependent on the UK as a market than the UK is on it

Looking beyond export revenues, hard Brexit would have a number of other implications.

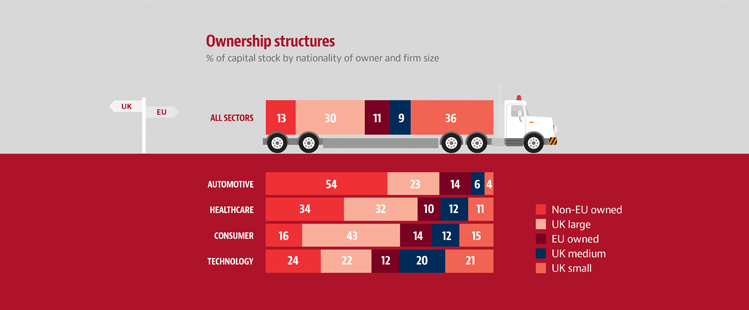

In many of the industries we modelled, there is a sizeable share of non-EU overseas ownership. These companies were likely motivated to base their operations in the UK because of the Single Market access it offered and they could seek to relocate if that market access is revoked. Over half of the automotive sector is owned by non-EU parent companies, while 44% of the healthcare sector is comprised of non-UK owned businesses.

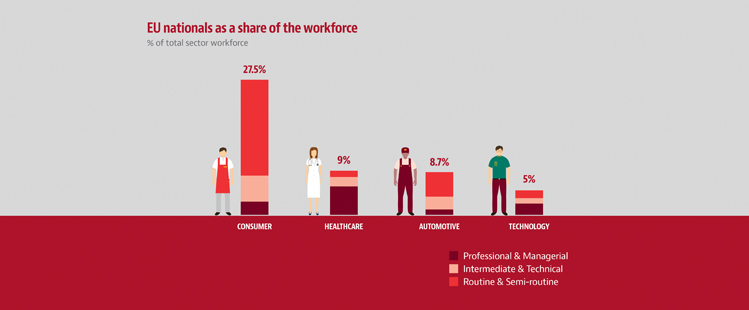

Meanwhile, the impact of hard Brexit on the labour supply would be felt most keenly in the consumer goods sector, where EU nationals provide more than 27% of the workforce. Those EU employees perform a wide range of roles, but the biggest proportion are in routine and semi-routine positions. The automotive sector faces a similar challenge, albeit on a smaller scale, while in the healthcare industry, concern lies not solely with the volume of staff that could be affected by tighter EU immigration controls, but with the proportion of senior staff whose positions may be in doubt post-Brexit.

Finally, as Brexit discussions begin to move beyond the EU, we consider where the best opportunities exist for trade with third countries – one possible answer to the losses associated with departing the Single Market.

“Organisations should start to focus on the different trade deals that may be on offer with third countries, to give the government a steer on what its priorities should be,” says Samantha Mobley, head of Baker McKenzie’s EU, Competition and Trade group in London. “They also need to consider their lobbying position on Europe vis-a-vis other FTA considerations. There may be inconsistencies between the requirements of continuing to do business with the EU and benefiting from trade treaties with third parties.”