On October 7, 2017, the EU Commission published its updated study on corruption in the EU healthcare sector. The study covered all EU Member States but focused on Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania. The study mainly investigated what the Member States could or should do to prevent corruption. However, the findings are equally relevant for companies. Companies in the healthcare industry should rethink their policies and procedures based on the results of this Europe-wide study.

I. Regarding the Healthcare Study

In 2012, the EU Commission (Directorate General Home Affairs) launched a study on the corrupt practices in the EU healthcare sector (2012 Study) in cooperation with Ecorys.[1] The aim of the 2012 Study was to obtain a better understanding of the scope, nature and effect of corruption in the healthcare sector within the EU and to assess the ability of the Member States to prevent and control corruption as well as the effectiveness of such measures in practice.

In 2016, the EU Commission requested an update of the 2012 Study. The objectives were:

- to analyze and report on relevant developments since the publication of the 2012 Study and

- to provide an in-depth analysis of selected issues such as

- privileged access to medical services,

- improper marketing and

- potential risks involving double practice.[2]

The updated study (2017 Study) covered all 28 EU Member States focusing on Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania.[3]

II. The results

The 2017 Study concluded that the healthcare sector is one of the areas that is particularly vulnerable to corruption. The results of the study relevant for companies in the healthcare sector were that

- bribery in medical service delivery remains one of the main challenges, especially in many Eastern and Southern European Member States.

- transparent procedures are key in addressing corruption in procurement processes.

- attempts to address improper marketing increase at both EU and national level.[4]

The study identified six typologies of corruption:

- bribery in medical service delivery;

- procurement corruption;

- improper marketing relations;

- misuse of (high) level positions;

- undue reimbursement claims;

- fraud and embezzlement of medicines and medical devices.

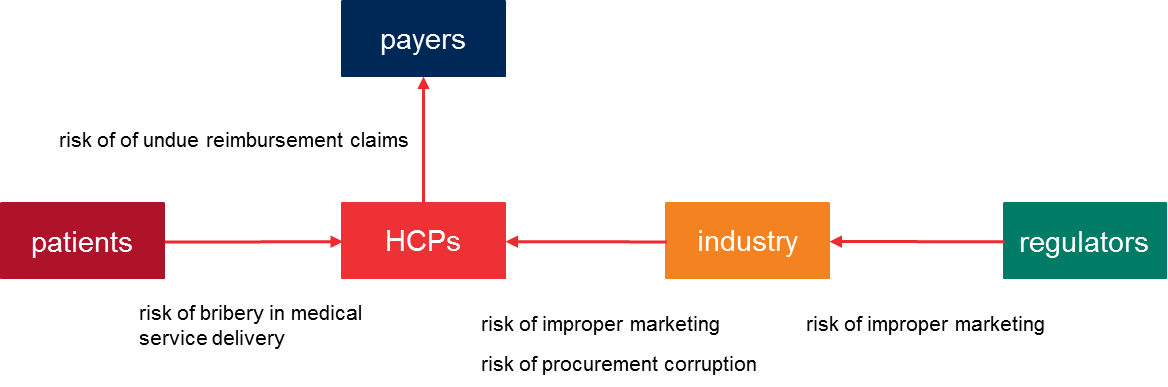

In relation to the involved parties, the corruption risks are allocated as follows:

For companies in the healthcare industries the main corruption risks are improper marketing and corruption to influence procurement decisions.

1. Countries take different measures to combat corruption in procurement of medical devices and pharmaceuticals

The 2012 Study concluded that corruption in procurement often took place during the early stages of the procurement process. A common way to influence procurement decisions was to tailor the tender specifications or the tender phase to one (preferred) supplier.

A suggested countermeasure was to centralize the procurement processes and to make the process transparent. A centralization in turn comes with risks.

The 2017 Study found that several Member States have implemented other measures to reduce the risk of corruption in the procurement of medical devices and pharmaceuticals. Croatia and Lithuania now publish the procurement data online. In Lithuania, the Ministry of Health is also encouraging hospitals to collaborate when purchasing pharmaceuticals or medical devices. In Romania and Greece, anti-corruption bureaus/directorates have been established to investigate corruption in connection with procurement decisions. Greece introduced a price observatory for medical supplies which indicates the maximum prices that can be charged to hospitals.[5]

2. Attempts to address improper marketing increase at both EU and national level

The 2017 Study states that the relationships between physicians and the industry contribute to the product development and the observation of the use of medicines in practice. In addition, the industry supports continuous medical education of healthcare professionals through sponsorship. However, these relationships may increase the risk of corrupt practices, such as influencing prescribing behavior. Such practices can lead to inefficient allocation of resources or even healthcare risks when certain medicines or devices are prescribed or used for reasons other than proven medical indications.[6]

Improper marketing – in both the pharmaceutical and medical devices sectors – was identified as one of the main types of corruption. The 2012 Study also revealed that both at the Member State and the EU level different measures were implemented to prevent and control this form of corruption. Despite those efforts, the 2017 Study showed that improper marketing remains a major challenge occurring often in many countries.

To prevent improper marketing, several (self-)regulation initiatives have been introduced. At the EU-level, the trade associations EFPIA (pharmaceuticals) and MedTech Europe (medical devices) have both introduced new codes. EFPIA published the ‘Disclosure Code’ which requires its members to disclose the transfers of value given to healthcare professionals and officers. MedTech Europe introduced the Code of Ethical Business Practices, which came into effect on 1 January 2017. One of the main prerogatives of the Code of Ethical Business Practices is to phase out direct sponsoring.

Further, initiatives have also been taken on national level. In many countries, national associations have introduced a code of conduct or ethics or transparency enhancing initiatives.

3. Spotlight on Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania

3.1 Croatia

The 2017 Study identified mainly corruption risks which relate to bribe payments by patients. However, the 2017 Study also highlights the X affair in 2013 which led to the conviction of 313 persons including physicians, pharmacists and managers and employees of a pharmaceutical company who were involved in this wide-spread bribery case.[7]

3.2 Greece

For Greece, the 2017 Study reported the following forms of corruption which are relevant to companies in the healthcare sector:

- Improper marketing – direct sponsorship is still allowed under Greek law but several larger companies have banned this behaviour as unethical.

- Corruption in procurement of medical devices and pharmaceuticals – Multiple cases have occurred in Greece which led to the establishment of a central procurement body. Since the body is not functioning properly, hospitals circumvent the centralized process.[8]

The 2017 Study detected several recent corruption cases which indicates that the pressure on corrupt individuals and companies is increasing.

3.3 Hungary

In November 2017, Hungary will put in place an electronic healthcare system which will create more transparency and allow patients but also the government to analyse the treatment related information.[9]

The main areas of corruption are public procurement and EU funds projects. In 2016, Transparency International found that public procurement procedures are 20 – 25 % more expensive than they should be because of corruption.[10]

In 2016, the Economic Competition Office imposed penalties on a few hospitals in Budapest and a pharmaceutical company which had colluded in a public procurement procedure.[11]

3.4 Lithuania

The 2017 Study identified corruption in connection with public procurement decisions as the main area of concern. Lithuania does have a central procurement system in place but it has not been mandatory to use it. At the same time, Lithuania lacks regulatory framework to tackle improper marketing activities.[12]

Over the past two years, five corruption cases in the healthcare sector became public in Lithuania including one case which involved the then Minister of Health and ultimately led to her resignation. The high number of cases may be a result of the various anti-corruption programs focusing on the healthcare sector in Lithuania. Most of the implemented measures focus on creating awareness and increasing transparency. For example, in 2014 the Ministry of Health introduced a ban on gifts from pharmaceutical sales representatives to physicians, which are not related to the professional activities of the physician. The pharmaceutical sector in Lithuania has also put in place several self-regulatory measures to prevent corruption including an ethical code and a disclosure code.[13]

3.5 Poland

The 2017 Study found that corruption in public procurement decisions is quite common in Poland, especially in connection with high tech medical equipment. Often physicians ask the medical service providers to assist them in drafting the tender specifications. Consequently, the specifications become too detailed that the assisting provider can be successful in the bid.[14]

Several initiatives led to more self-regulation to avoid improper marketing. Certain codes were adopted at government and industry level.[15]

The 2017 Study reported 8 cases – 7 of which in 2016 and 2017 – of corruption in the healthcare sector which were prosecuted.[16]

Since the 2012 Study, Poland has introduced several initiatives to prevent corruption, e.g. the adoption of an anti-corruption plan, initiatives within the government to prevent corruption, patient-related initiatives and self-regulation in the industry.[17]

3.6 Romania

In Romania, the perceived levels of corruption are highest in healthcare.[18] Corruption is widespread and occurs among all risk areas, including corruption in public procurement decisions and illegal sponsorships. The National Agency for Public Procurement estimates that 25 to 30 % of public procurement contracts are suspected of fraud or corruption, including the practice to split large contracts to stay below tender thresholds.[19]

At the same time, the National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA) has targeted corruption in the healthcare sector intensively over the past five years. Since 2012, the DNA has investigated 54 cases involving corruption in the healthcare sector, 23 of which in 2016. The underlying charges showed a variety of offenses. 18 of the 54 cases involved corruption in public procurement processes.[20]

4. Study emphasizes regulatory developments in Germany

The 2017 Study highlights the new sections on bribery in the healthcare sector in the German Criminal Code which was introduced in April 2016. The bill introduced criminal liability under the new section 299a of the German Criminal Code where a healthcare professional in relation to his occupation, demands, allows himself to be promised or accepts a benefit for himself or another for according an unfair preference in domestic or international competition when prescribing or procuring pharmaceutical products, or when introducing patients. Vice versa, those who offer, promise or grant a benefit to a healthcare professional under these circumstances will be criminally liable pursuant to section 299b of the German Criminal Code. See our previous post for further information.

III. Conclusion

Corruption in the healthcare sector of the EU still remains a critical issue. There are multiple initiatives from public and private institutions underway to tackle the identified key areas of corruption. Companies should closely monitor the developments in the jurisdictions in which they operate. The results of the 2017 Study on the six focus countries could be a good start to review the policies and procedures applicable to the respective entities.

[1] For more information please see at https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-is-new/news/news/docs/20131219_study_on_corruption_in_the_healthcare_sector_en.pdf

[2] For more information on the updated Study please see at https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/20170928_study_on_healthcare_corruption_en.pdf

[3] The Study took also in consideration the findings from the Special Eurobarometer 397 on Corruption, reports on Corruption in Healthcare from Transparency International, EC report on Health Care and Long Term Care Systems & Fiscal Sustainability as well as Healthcare in Transition reports and OECD publications.

[4] 2017 Study, page 9.

[5] 2017 Study, page 146.

[6] 2017 Study, page 147.

[7] 2017 Study, page 49.

[8] 2017 Study, page 38.

[9] 2017 Study, page 69.

[10] 2017 Study, page 71.

[11] 2017 Study, page 72.

[12] 2017 Study, page 56.

[13] 2017 Study, pages 58, 59.

[14] 2017 Study, page 81.

[15] 2017 Study, page 81.

[16] 2017 Study, pages 82, 83.

[17] 2017 Study, page 84.

[18] 2017 Study, page 93

[19] 2017 Study, page 95.

[20] 2017 Study, page 97.