In brief

Unlike in other jurisdictions, straightforward corporate power purchase agreements (PPA) are not possible in Indonesia, as only the Indonesian state-owned power utility PT PLN (Persero) (PLN) and private power developers that have the relevant business area approval can sell electricity to end customers. As a result, there is a general perception among developers and corporates alike that it is not possible to implement corporate PPA structures in Indonesia. In fact, this is not the case, and as the Government of Indonesia makes a big push for rooftop solar schemes, we expect to see an uptick in structures that enable private developers to arrange for electricity generation to customers.

Contents

Background

The whole territory of the Republic of Indonesia falls within the business area of the state electricity company, PLN. The Government has the authority to carve out parts of this business area from PLN’s territory and give them to other companies. In practice, these business areas typically can be granted if the area is an industrial estate, or is in a remote area where PLN’s grid is not available. But it can be very difficult for investors to obtain a business area stipulation if PLN supply is already available.

Companies that are looking into having “captive power plant” arrangements have been faced with the difficulty that under Indonesian law, “captive” power plants actually means that the companies will need to develop the power plants by themselves, solely to generate electricity for their own use.

Structure

While in the context of Indonesia’s regulatory framework, corporate PPA structures raise a number of issues, such structures are doable here. We have seen a number of structures utilized, among others, operating leases, equipment supply/manufacture agreements that involve cooperation with an existing finance company, equipment supply/manufacture and acquisition of existing finance company arrangements, equipment supply/manufacture with loan financing and offshore leases.

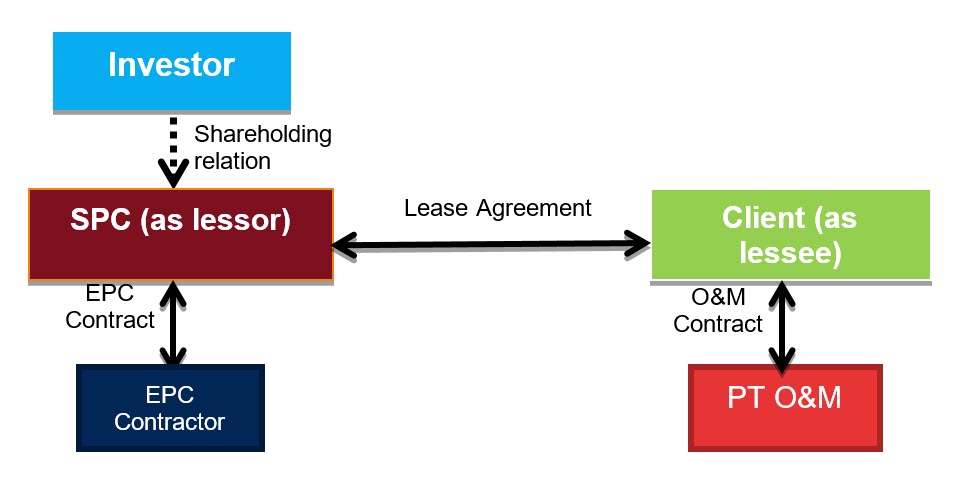

However, the most frequently used “corporate PPA” scheme in Indonesia is a relatively straightforward operating lease arrangement, where a power developer leases its power plant to a consumer, with the rental fee being structured in a similar way to the conventional power purchase agreement with PLN. A typical structure is shown below:

Although relatively straightforward, the above structure raises a number of issues to be further considered, including the following:

1. Foreign ownership limitations

Previously, there was an ambiguity as to whether power equipment rental was open or closed for foreign ownership. Traditionally, foreign investment companies in Indonesia could not engage in pure (dry) rental business activities. The same was true of power equipment rental.

Power equipment rental is no longer listed under the new Positive List (issued in 2021), and it is therefore theoretically 100% open for foreign ownership.

2. Rental Fees

Rental fees are not subject to any governmental authority’s approval. In practice, developers tend to refer to the amount of energy generated from the power equipment (in kWh) as the basis for determining the monthly rental fee. However, we have seen concerns being raised that rental fees should not too closely resemble the tariff structure for sale of electricity.

3. Main licenses and approvals

A captive power license (previously known as an operational license or izin operasi, currently known as an electricity supply business license for own use or IUPTLS) is required if the installed capacity of the plant is higher than 500kW per electrical power installation.

An SLO (operational worthiness certificate) is also required for a captive power plant with a capacity of more than 500 kW. Specifically for captive solar PV projects, an SLO is required for a solar PV system with a capacity of (i) more than 500 kW (with an integrated panel control) and (ii) up to 500 kWh (with an independent panel control). The corporate customer (i.e., the lessee) will need to obtain these licenses.

The developer will need to secure a general trading company license.

For solar PV projects, the business area holder’s approval of the design of the plant will be needed before construction. See our alert for further details.

4. Parallel operation charges

Industrial customers with solar PV projects that are connected to a business area holder’s grid will be subject to a capacity charge in an amount equivalent to: 5 hours × capacity of the solar PV project (at inverter) × the business area holder’s tariff for the customer (in IDR / kWh).

For other types of captive power projects (non-solar PV), the customer may be subject to higher parallel operation charges.

The implications of these charges for any future development will need to be taken into account by developers and customers.

5. Transfer of assets

Any transfer of assets following the rental term might be considered as a financial lease, in which case the developer will be subject to the rules of the Financial Services Authority. The corporate PPA will need to be drafted carefully to mitigate this risk.

6. Local content

The Omnibus Law now requires state-owned enterprises, regional-owned enterprises, private companies, cooperatives, and non-government organizations to prioritize domestic products and domestic potential in carrying out an electricity supply business for the public interest. Separately, the newly issued MEMR Regulation No. 26 of 2021 on solar rooftops also requires the use of rooftop solar PV equipment to comply with laws and regulations on the use of domestic goods/services. It remains to be seen to what extent these requirements will capture corporate PPA schemes.

7. Limit on capacity for solar PV projects

For PLN customers with on-grid solar PV projects, the maximum capacity of the solar PV systems (at the inverter) is equal to the customer’s connected capacity with PLN. For non-PLN customers, the relevant business area holder will have the discretion to determine the maximum capacity of the solar PV projects.

Conclusion

Although the arrangements described above have been a relatively common feature in the conventional power sector, in the last three years we have seen the growth of these structures in the renewable energy sector, led by non-industrial corporate purchasers. As corporates look for ways to further enhance their ESG commitments, we expect further use of these, and similar, structures.