In brief

The United States tax treaty with Chile has finally been approved by the Senate, over a decade after its original signature on 4 February 2010.

In more detail

On 22 June 2023, the Senate voted 95-2 to pass the resolution of advice and consent to ratification of the Convention Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Chile for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income and Capital (“Treaty”). The Treaty now heads to the President for official ratification.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee also released its accompanying Executive Report, which includes an overview of key provisions and the Technical Explanation of the Treaty, which serves as the official explanation of the United States’ interpretation of the Treaty.

As noted above, the Treaty was originally signed in 2010, and has, like many other US tax treaties, sat in treaty purgatory for the past decade. Other than a brief detente in 2019, no US tax treaty had been approved by the Senate in nearly a decade. Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) has blocked progress on these conventions due to his objection to the exchange of information provisions common in US tax treaties. The Treaty was part of a package of other conventions that the Senate Foreign Relations Committee previously approved in 2014, 2015, and 2016, but it was not put to a vote in the Senate due to Senator Paul’s objections. Similarly, the Treaty was approved by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in March of 2022, but did not receive a vote before the full Senate, requiring the process to restart in 2023.

Notably, the Treaty was not included in the package of treaties ratified in 2019 because the Senate Foreign Relations Committee sought to include two reservations to the Treaty relating to changes in US domestic law under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA). The first reservation preserves the United States’ right to impose the Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT). Specifically, this reservation allows the United States to impose the tax under Code section 59A on companies resident in the United States or on the profits of a company resident in Chile that are attributable to a US permanent establishment. This reservation appears to be in response to arguments that the BEAT is inconsistent with US tax treaties. One such argument was that the BEAT was in violation of the non-discrimination provisions because it placed residents and non-residents on unequal footing with respect to the ability to take deductions. In addition, the BEAT potentially violated the provisions requiring the United States to provide relief from double taxation because it could have the effect of denying foreign tax credits. This reservation thus clarifies that the Treaty should not bar the United States from imposing the BEAT.

The second reservation, which was also raised to reflect TCJA provisions, amends the relief from double taxation provisions in Article 23 to take into account the repeal of the indirect tax credit with respect to dividends from foreign subsidiaries. Such dividends now benefit from dividends received deduction under Code section 245A. Thus, this reservation modifies the relief from double taxation language to allow the United States to provide such relief either through a credit or through the dividends received deduction. As compared to the version of the Executive Report that accompanied the Treaty when voted out of committee in 2022, the section of the 2023 Executive Report that describes this reservation included a modified summary of this provision, and states that “the terms of the reservation and this report are not intended to create any inferences regarding the interpretation of existing tax treaties to which the United States is a party”.

The Senate Resolution also includes two declarations, one of which is new as compared to the proposed resolution from 2022. When the Treaty was last voted out of committee, it had a single declaration that provided that the Treaty is self-executing. This means that the United States need not pass implementing legislation in order for the Treaty to become part of US law. This declaration is simply standard language included for the avoidance of doubt. The new, second declaration expresses the Senate’s position that further work is required with respect to the “Relief from Double Taxation” articles in future tax conventions in light of the substantial changes made to the Code in the TCJA.

The Treaty goes into effect only after ratification by both the US Senate and the Chilean government and after both the United States and Chile have notified each other that they have completed all necessary procedures required for entry into force. Even then, however, the Treaty includes different effective dates for different provisions. The Treaty will have effect with respect to taxes withheld at source for amounts paid or credited on or after the first day of the second month following the date of entry into force. For example, if the Treaty enters into force on 30 July, these provisions would go into effect 1 September. The Treaty will have effect with respect to all other taxes for taxable years beginning on or after 1 January of the calendar year immediately following the date of entry into force. Thus, if the Treaty enters into force this year, it will be effective for calendar year taxpayers beginning 1 January 2023, and for fiscal year taxpayers upon the beginning of their next taxable year after 1 January 2023.

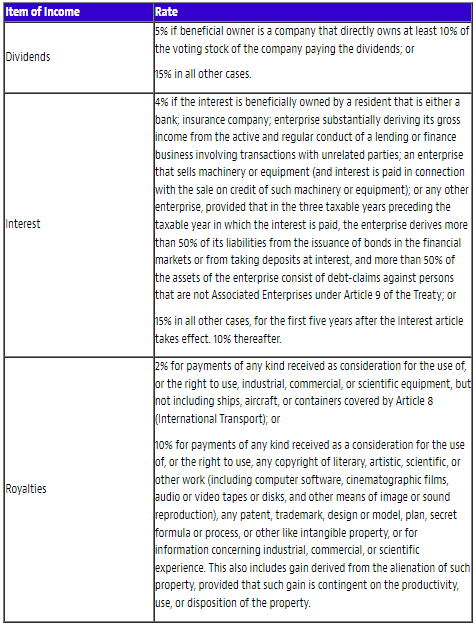

The Treaty generally aligns with the 2016 US Model Income Tax Treaty. The Treaty reduces the rates of withholding on dividends, interest, and royalties as follows:

Unlike more recent US tax treaties, the Treaty does not include mandatory binding arbitration as part of its mutual agreement procedure. Taxpayers may present their case to the competent authority of the Contracting State in which they are resident within three years from the first notification of the action resulting in taxation not in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty.

The Treaty includes a standard Exchange of Information article. In addition, the Protocol provides that, irrespective of the date the Treaty enters into force, certain Chilean information dating back to 1 January 2010 will be made available. In addition, other information like signature cards and other account opening documents may be exchanged without regard to the time they were created.