On July 8, 2016 the Dutch Supreme Court referred questions for a preliminary ruling to the European Court of Justice (ECJ), asking whether certain elements of the Dutch fiscal unity regime should also be available to Dutch resident companies with a 95% or more EU resident parent, subsidiary or sister company which can not be part of a Dutch fiscal unity due to the geographical restrictions of the fiscal unity regime. The cases at hand relate to the application of a specific anti-abuse rule on interest deductions and the non-deductibility of foreign exchange losses in relation to a subsidary. The ECJ can take up to two years time to issue the final ruling. In the meantime, companies are encouraged to assess whether any fiscal unity related tax advantages have been unavailable to them, only because of the fact that the Dutch fiscal unity regime is restricted to Dutch resident companies and therefore an EU resident parent, subsidiary or sister company could not be included in a fiscal unity. A (non exhaustive) list of examples of such advantages includes:

- Non applicability of interest deduction limitation rules;

- Deductibility of foreign exchange losses arising from foreign participations;

- Non applicability of liquidation loss limitation rules;

- Non applicability of holding loss ring-fencing rules;

- No recognition of income and capital gains on transactions within a fiscal unity;

- Non applicability of certain restrictions in the innovation box regime

1. Background & Relevance

The Dutch Supreme Court referred questions for a preliminary ruling to the ECJ to determine whether certain benefits of the Dutch fiscal unity (i.e. group taxation) regime should also be available to Dutch resident companies with a 95% or more EU resident parent, subsidiary or sister company. In its earlier judgment X-Holding (C-337/08), the ECJ ruled that the Dutch fiscal unity regime does not have to allow the inclusion of an entity in another EU member state in the Dutch tax consolidation. However, following the ECJ’s judgment in the (French) case Groupe Steria (C 386/14), the question arose whether certain benefits of the Dutch fiscal unity regime must still be granted to a Dutch resident company, without actually including an entity that is resident in the other EU member state in the Dutch tax consolidation based on the so called ”per-element approach”. The fundamental question which the ECJ must now decide on, is whether this per-element approach should also be applied in relation to the Dutch fiscal unity regime.

2. Examples based on the referred cases

If the ECJ rules that the per-element approach must also apply to the Dutch fiscal unity regime, this could be beneficial for Dutch taxpayers in for example the following situations.

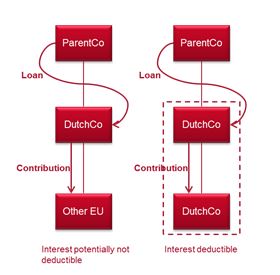

(i) If a Dutch company borrows monies from a group company, and uses the monies to contribute capital to an EU resident subsidiary, the interest expense deduction could be denied on basis of a specific anti-abuse rule. If the EU resident subsidiary would have been a Dutch resident company, a fiscal unity could have been formed. As a result, the capital contribution would have been eliminated in the fiscal unity consolidation. Hence, the limitation of interest expense deduction rule would not have been applicable. If these two situations are considered comparable, there is a discrimination under EU law, and the question arises whether this different tax treatment can be justified. If there is no justification for the discrimination, both situations must be treated the same.

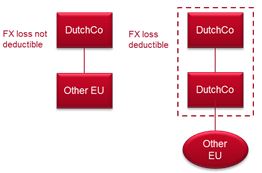

(ii) A Dutch parent company may suffer a foreign exchange loss arising from a shareholding in for example a Polish subsidiary. Such exchange loss is not deductible on the basis of the participation exemption. However, if the activities in Poland would have been carried on by a Dutch subsidiary company through its Polish permanent establishment, the foreign exchange loss would be deductible if that Dutch subsidiary is included in a fiscal unity with its Dutch parent company. If these two situations are considered comparable, there is a discrimination under EU law, and the question arises whether this different tax treatment can be justified. If there is no justification for the discrimination, both situations must be treated the same.

3. What to do?

If your Dutch company forms part of an international group and one or more benefits of the Dutch fiscal unity regime are currently unavailable to your Dutch company, while these benefits could have been available if the EU parent company, EU subsidiary or EU sister company would have been a Dutch resident company eligible for the Dutch fiscal unity regime, we recommend to further look into the missed benefits and take necessary actions to preserve your rights pending the ECJ case. We would be happy to assist you with that.