In brief

Since 2013, even if the interest income from a loan to an affiliated company in Sweden was taxed at a rate of at least 10% in the lender’s country of residence, the interest deduction was often disallowed on the ground that the principal reason for the debt having arisen was for the group to receive a substantial tax benefit. Last Wednesday, 20 January 2021, the ECJ ruled that it is contrary to EU law to deny interest deduction on cross-border loans on this ground if the interest would have been considered deductible if the lender had been a Swedish entity. This landmark ruling provides companies the possibility to reassess non-deductible interest costs in Sweden.

Key takeaways

We advise our clients to consider whether deduction of interest on intragroup loans was disallowed in Sweden during 2015 to 2019 and whether it would be beneficial to seek a reassessment of the disallowed interest in light of the ECJ ruling. The statute of limitation for reassessment of the STA’s decisions and negative court judgments in light of new case law from the Supreme Administrative Court is six years, which means that decisions and judgments regarding fiscal years 2013 to 2014 are excluded from reassessment.

Background

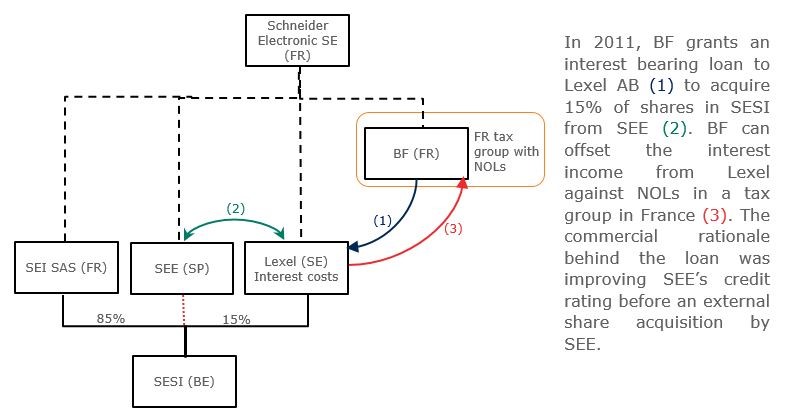

Swedish limited liability company, Lexel was granted an interest-bearing loan in 2011 by its group finance company BF (France) in order to finance acquisition of 15% of shares in an affiliated entity SESI (Belgium) from another group company SEE (Spain). BF could offset the interest income from Lexel against losses in a tax group in France. The business reason for the loan was improving SEE’s credit rating before an external share acquisition by SEE. The Swedish Tax Agency (STA) denied the interest deduction for Lexel for 2013 and 2014 on the basis that the principal reason for the debt was to receive a substantial tax benefit. It was uncontested that BF was the beneficial owner of the interest income and that the income would have been taxed at a rate of at least 10% should it have been the only income of BF. However, the STA argued that the intragroup acquisition of shares in SESI was not justified by sound business reasons and that the main reason for the transaction was to receive an interest deduction in Sweden instead of Spain. Since the interest income was offset against losses in France, the interest income was, in principle, not subject to taxation, giving rise to a substantial tax benefit for the group.

The Swedish interest deduction limitations apply in both domestic and cross-border situations, but if there are no limitations on entitlement to profit shifting through group contributions between Swedish companies, internal debt financing will not be mainly tax motivated. This is because those Swedish companies would have been able to achieve similar deductions by making group contributions. Therefore, in domestic cases where it is possible for the lender and borrower to exchange group contributions, the interest deduction limitation rules will not come into play. Foreign companies are not allowed to become part of a Swedish taxation group and exchange group contributions unless they have a permanent establishment in Sweden. In cross-border situations, the interest deduction limitation restricts a transfer of untaxed profits from Sweden to other Member States. In practice, the tax benefit restricting deductibility of interest expenses could only be identified in cross-border loans, since Swedish group companies can consolidate tax through tax-deductible group contributions. Therefore, an additional deduction through interest expenses would not give rise to any tax benefits. The rules deny a Swedish subsidiary a tax-effective deduction of interest expenses paid on an intragroup loan if the lender is an affiliate company resident in another Member State, whereas a full deduction is given if the internal lender is a Swedish group company. The ECJ ruled in C-484/19 that this difference in treatment of interest for Swedish and foreign lenders constituted an infringement of the freedom of establishment, which cannot be justified by the need to safeguard a balanced allocation of the power to impose taxes between Member States or the need to fight against tax evasion and fraud. The case has now been referred back to the Supreme Administrative Court in Sweden, which should render its final decision shortly.

The ECJ ruling brings a sought-after clarification on the interpretation of “substantial tax benefit” under the Swedish interest deduction limitation rules. For years the Swedish courts have ruled that the infringement on the right of establishment was compatible with EU law because it could be justified by the need to fight against tax evasion. The application of the interest deduction limitation rules and the case law built around it has led to disallowing many Swedish companies deduction on interest expenses on loans from their foreign subsidiaries. The question put forward in the ECJ concerns freedom of establishment and is thus not directly applicable to interest paid to lenders resident outside of the EU.

If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact us.