In brief

In the not too distant past, many were convinced that Artificial Intelligence (AI) or Machine Learning (ML) would not substantially change the practice of law. The legal profession was considered to be — by its very nature — requiring specialist skills and nuanced judgment that only humans could provide and would therefore be immune to the disruptive changes brought about by the digital transformation. However, the application of ML technology in the legal sector is now increasingly mainstream, particularly as a tool to save time for lawyers and provide a richer analysis of ever-larger datasets to aid legal decision-making in judicial systems throughout the world.

In more detail

One key area of ML application in judicial systems is in “predictive justice”. This involves using ML algorithms that perform a probabilistic analysis of any given particular legal dispute using case law precedents. In order to work correctly, these systems must rely on huge databases of previous judicial decisions which have to be translated into a standardized language that, in turn, is able to create predetermined models. These will ultimately help the machine learning software generate the prediction.

Does this technology mean trials ending at the speed of the light, lawyers being able to know in advance whether or not to start a lawsuit, courts immediately deciding a case? Well, there is still a long way to go and we need to also balance the risks inherent to the use of these technology tools. For example, the data used to train the ML system could result in bias and consolidate stereotypes and inequality that would be validated merely because they were produced several times by the AI. Watch out, then, for possible added complexity in creating new precedents and case law against all the odds!

To assess the opportunities and challenges brought about by predictive justice systems using ML tools, it is instructive to look at case law examples, as often history is a proxy to understand the future.

Machine Learning in judicial systems

The first time “predictive justice” started to see the light was in the United States way back in 2013 in State v. Loomis where it was used by the court in the context of sentencing. In that case, Mr. Loomis, a US citizen, was charged with driving a car in a drive-by shooting, receiving stolen goods and resisting arrest. During the trial, the circuit court was assisted in its sentencing decision by a predictive machine learning tool and the ultimate result was the judge imposing a custodial sentence. Apparently, the judge was convinced by the fact that the machine learning software tool had suggested there was a high probability that the defendant would re-offend in the same manner.

On appeal, the Supreme Court of Wisconsin affirmed the legitimacy of the software as the judge would have reached the same result with or without the machine learning software. The decision included finding that the risk assessment provided by the AI software, although not determinative in itself, may be used as one tool to enhance a judge’s evaluation, weighing in the application of other sentencing evidence when deciding on appropriate sentencing for a defendant.

In essence, the Supreme Court of Wisconsin recognized the importance of the role of the judge, stating that this kind of machine learning software would not replace their role, but may be used to assist them. As we can imagine, this case opened the door to a new way of delivering justice.

Indeed, fast forward to today and we read about news from Shanghai telling us the story of the first robot ever created to analyze case files and charge defendants based on a verbal description of the case. AI scientists honed the robot using a huge amount of cases so that the machine would be able to identify various types of crimes (i.e., fraud, theft, gambling) with a claimed 97% accuracy.

AI-based predictions used to assist the courts are increasingly prevalent and may raise significant concerns (including bias and transparency). Several regulatory authorities are cooperating to advance a set of rules, principles and guidance to regulate AI platforms in judicial systems and more generally.

For example, in Europe, a significant step towards digital innovation in judicial systems was taken with the creation of the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) which published the “European Ethical Charter on the use of Artificial Intelligence in judicial systems and their environment“, one of the first regulatory documents on AI (“Charter“). The Charter provides a set of principles to be used by legislators, law professionals and policymakers when working with AI/ML tools aimed at ensuring that the use of AI in judicial systems is compatible with the fundamental rights, including those in the European Convention on Human Rights and the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data.

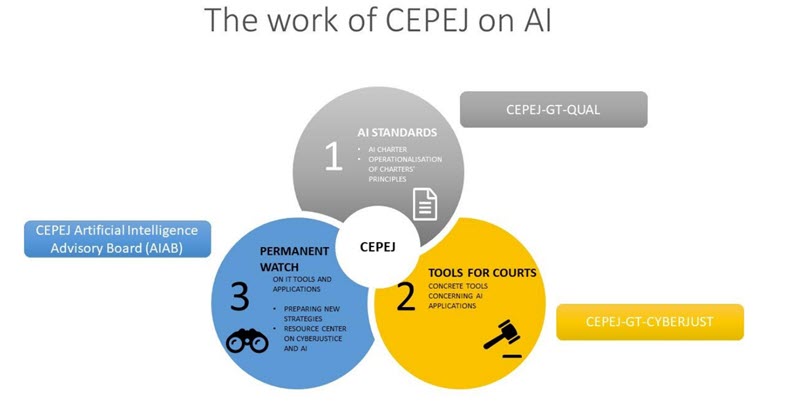

Recently, CEPEJ has laid down its 2022 to 2025 Action plan for the “Digitalisation for a better justice” identifying a three-step path aimed at guaranteeing a fair use of AI in courts as per the visual representation below:

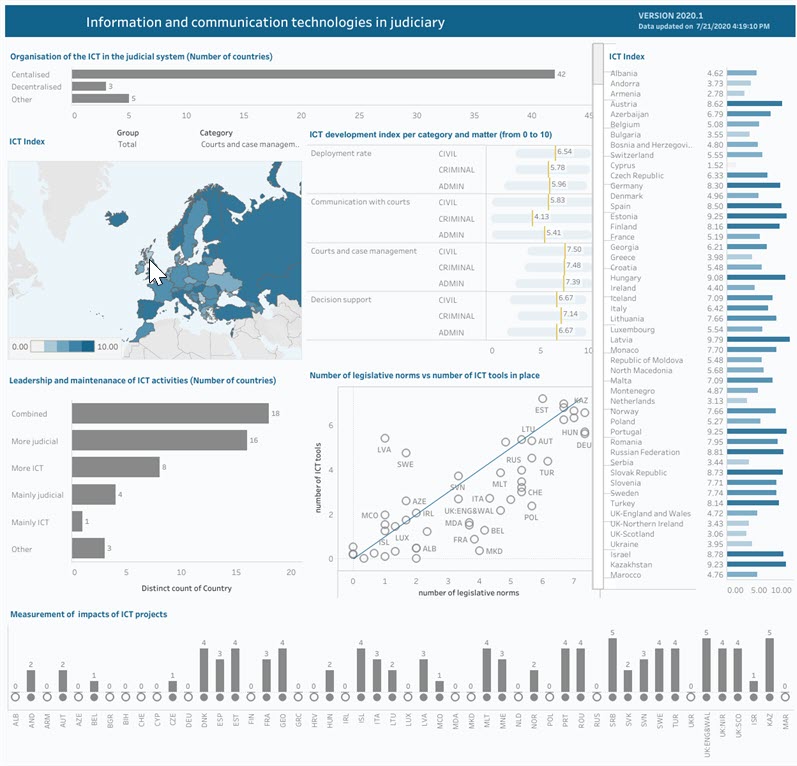

CEPEJ’s commitment does not stop there. Indeed, the table below shows a glimpse of how information technology tools are catching on in the judicial systems of the EU Member States (civil and criminal) and how the use of IT in EU courts is accelerating.

Source: Dynamic database of European judicial systems.

More broadly, the European Commission is currently focused on developing a set of provisions to regulate AI systems which are outlined in a draft AI Regulation (“Regulation“) published in 2021. The Regulation proposes harmonized rules for applications of AI systems. It follows a proportionate risk-based approach differentiating among prohibited, high-risk, limited and minimal-risk uses of AI systems. Regulatory intervention, therefore, increases along with the increase in the potential of algorithmic systems to cause harm. For more, see our alert New Draft Rules on the Use of Artificial Intelligence.

AI systems used for law enforcement or in the administration of justice are defined as high-risk AI systems under the Regulation. Note that the use of real-time biometric identification systems in public places by law enforcement is (subject to certain exceptions) prohibited. High-risk AI systems are subject to requirements, including ensuring the quality of data sets used to train the AI systems, applying human oversight, creating records to enable compliance checks and providing relevant information to users. Various stakeholders, including providers, importers, distributors and users of AI systems, are subject to individual requirements, including in relation to compliance of the AI systems with the requirements of the Regulation and CE marking of such systems to indicate conformity with the Regulation.

The Regulation has still a long way to go before being finally approved and becoming binding on Member States, but it is already a step forward in regulating AI — not only as it may be used in the administration of justice, but as it may also impact deeply on the way we work, communicate, play, live in the digital era.

Camilla Ambrosino has helped in preparing this editorial.

This article was originally published in the January 2022 edition of LegalBytes.