In brief

On 15 March 2024 a new compromise proposal of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) was agreed upon by the EU Member States. The CSDDD sets out human rights and environmental due diligence obligations for companies within and also outside of the EU. Some key regulations have been eased in order to reach an agreement and pave the way for passing the law. As a next step the European Parliament has to adopt the Directive before the Member States will have to transpose the Directive into national law.

As one of few Member States Germany already took a step towards responsible supply chains in early 2023 with the Act on Supply Chain Due Diligence (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz – LkSG). In this blog post we discuss the key differences between the LkSG and the updated CSDDD text and highlight where the LkSG will likely be amended when transposing the CSDDD.

Contents

- Scope of application

- Phased Implementation

- From Supply Chain to Chain of Activities

- Due Diligence measures

- Introduction of civil liability

- Stricter sanctions

- Climate focus

- Takeaway

Scope of application

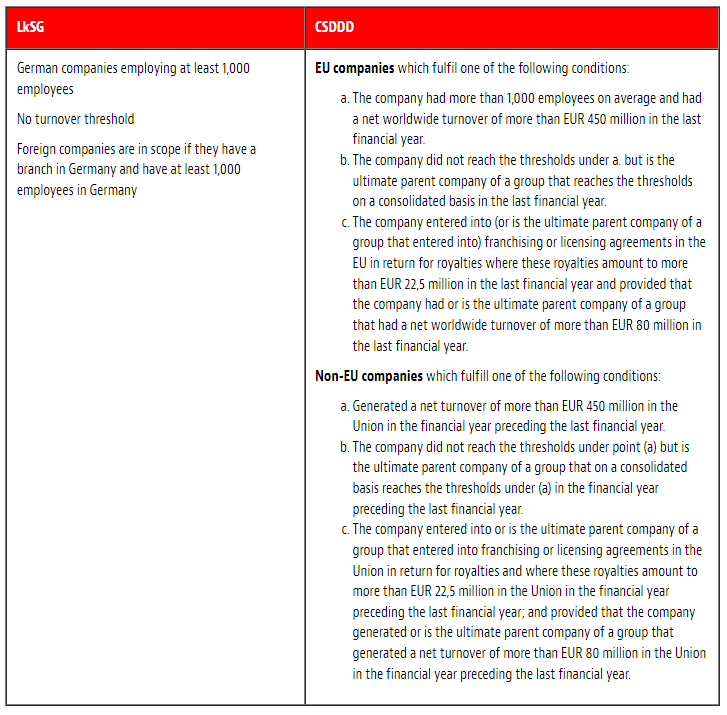

Compared to earlier drafts of the CSDDD, the thresholds for applicability have been increased in order to reduce the number of EU and non-EU companies that would fall under the scope of the Directive.

EU companies are in scope of the CSDDD if they have more than 1,000 employees and a turnover of EUR 450 million. The LkSG has the same employee threshold, but no turnover threshold. This leads to a narrower scope of applicability for the CSDDD than for the LkSG.

The CSDDD also addresses non-EU companies. Companies located outside of the EU are in scope of the CSDDD provided they generate a net turnover of more than EUR 450 million in the EU. This provision will need to be implemented in the LkSG: As for now, foreign companies are only subject to the LkSG if they have a branch office in Germany employing at least 1,000 employees.

Phased Implementation

However, a main element of the new compromise CSDDD is the phased implementation over the coming years giving companies more time to adjust:

- Companies with over 5,000 employees and a turnover exceeding 1.5 billion must comply within three years after the entry into force of the CSDDD, likely 2027.

- Companies exceeding 3,000 employees and a turnover above 900 million will have four years to adjust after the entry into force of the CSDDD, likely 2028.

Companies with more than 1,000 employees and a turnover exceeding 450 million will be granted the longest application period of five years after the CSDDD enters into force to comply, likely 2029.

From Supply Chain to Chain of Activities

In its scope of responsibility, the CSDDD goes beyond the LkSG. The term supply chain, as defined in the LkSG is limited to due diligence measures within the company’s own business area and its suppliers. The CSDDD broadens this scope to the so-called chain of activities. This means due diligence requirements will cover a company’s own business activities, as well as those of its subsidiaries, extending to both the upstream and certain downstream business partner activities.

The upstream chain of activities includes all activities of a company related to product manufacturing, such as raw material extraction, and provision of services.

The downstream chain of activities does not cover all downstream activities but rather only includes activities conducted by business partners regarding distribution, transportation and storage. With the latest update to the CSDDD the downstream part of the definition has been slightly eased by deleting the references to the disposal of the product.

With this, the CSDDD goes further than the LkSG when it comes to the area of responsibility. This will likely require amendments to the LkSG.

Due Diligence measures

Along their chain of activities, in-scope companies are required by the CSDDD to adopt and implement effective due diligence measures for identifying, preventing, mitigating, and ending potential and actual so-called adverse impacts on human rights and environmental matters.

These adverse impacts are specified by reference to international treaties ratified by Member States.

Adverse environmental impacts include inter alia impacts resulting from pollution, deforestation, excessive water consumption or damage to ecosystems.

Adverse human rights impacts are defined as impacts resulting from an abuse of one of the human rights listed in several international instruments. Typical examples include child labor, slavery, and labor exploitation.

Introduction of civil liability

Another key difference between the CSDDD and LkSG that remains with the new compromise is the liability risk. While the LkSG explicitly excludes civil liability, it is included in the CSDDD. The CSDDD enables affected parties to directly file claims against companies for damages stemming from intentional or negligent violations of their obligations to ensure effective enforcement. The CSDDD also requires the Member States to provide for reasonable conditions under which any alleged injured party may authorize a trade union, non-governmental human rights or environmental organization or other non-governmental organization and national human rights’ institutions based in a Member State to bring actions to enforce the rights of the alleged injured party. The possibility for civil liability will thus need to be incorporated into the LkSG.

Stricter sanctions

Under the CSDDD the EU Member States will have to lay down rules for sanctions in case of violations of the CSDDD obligations. Fines shall be based on the company’s net worldwide turnover. Pursuant to the CSDDD the maximum limit of pecuniary penalties shall be not less than 5 % of the net worldwide turnover of the company in the financial year preceding the fining, i.e., a fine can in practice be even higher than 5 % of the turnover if a Member State decides to transpose accordingly. In contrast, the LkSG currently provides for fines up to 2 % of the net turnover.

Climate focus

The CSDDD will further require companies to adopt and put into effect a climate transition plan for climate change mitigation in line with the Paris agreement and its aim to limit of global warming to 1.5 °C. The new compromise emphasizes that the requirement for a climate transition plan should be understood as an obligation of means and not of results. Companies thus have to prove their best efforts rather than reaching specific targets. To avoid duplicating reporting obligations, companies complying with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will be exempted from the obligation to adopt a climate transition plan as they already have to report a transition plan for climate change mitigation under the CSRD. Compared to the LkSG the CSDDD puts more focus on the environment and the EU’s climate goals

Takeaway

Despite the weakened scope of application compared to earlier drafts of the CSDDD, the Directive still provides for extensions compared to the LkSG. In summary, the CSDDD provides for stricter regulations in the following areas:

- Broadening the scope of affected entities without EU presence

- Extension of the covered supply chain to parts of the downstream chain of activities

- Enhanced liability paired with stricter sanctions

- Further focus on climate considerations

The learnings from implementing the LkSG serves as a valuable practice to prepare for the new CSDDD. Companies already compliant with the LkSG’s provisions are well on their way to tackle the CSDDD’s new challenges. With the adoption of the CSDDD on the horizon, Baker McKenzie is here to help. As experts in the field of ESG, compliance and investigations, we are committed to guiding clients through the evolving landscape of corporate accountability in supply chain management.